Perpetual Storage

Where does the data go?

Where does it go after you die, after the app company folds, after the powers of the world shift?

Your phone is a single generation of a very long line of obsolete devices. Your computer and its backup drive in your house is subject to fire, flood, or earthquake. An online backup provider is but one solution, each with an average corporate lifespan of 5.4 years (I made that up). "The Cloud" is a single corporate entity that you chose for your specific data. It's subject to regime change, incompetence, or malevolence. It stores your data in countries that may be taken over, in areas where a 1000 year flood may put it 20 feet underwater, turning your bits into powdery rust.

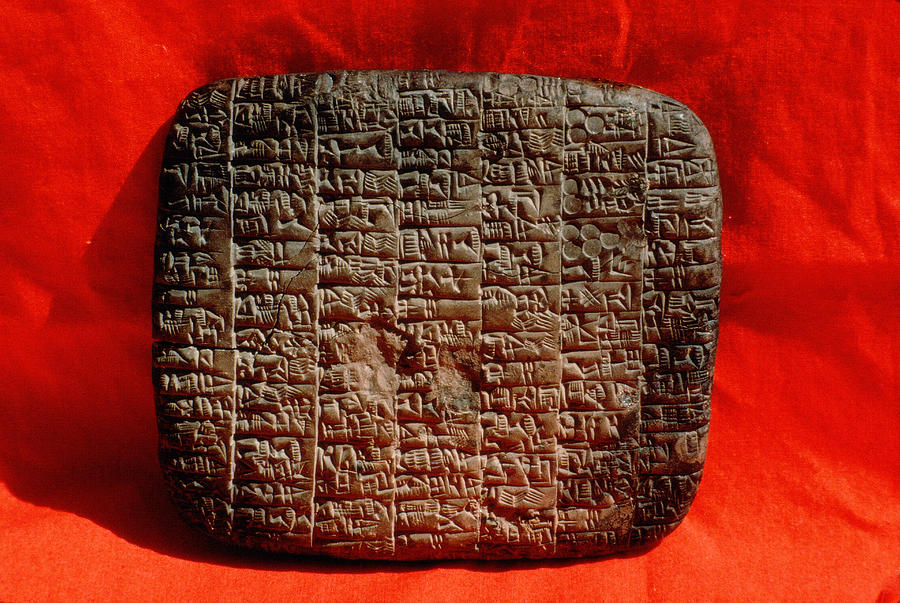

I think the answer to this question lies in what our earlier selves have taught us about passing information forward generation. The most successful have been stone carvings. Stone is far less susceptible to natural degradation than any organic fiber. Without stone carvings, we would not be able to predict when we achieved a level of intelligence.

Looking forward from stone, we moved to materials more suited to fast transcription. Those were the early days of papyrus as it evolved through paper, then to the printing press, then digitally to magnetic tape, magnetic discs, and solid-state storage devices. As we've produced exponentially more information, we've had to accommodate with exponentially capable media, both in terms of raw capacity, but also to ingest/output rates. We are optimizing for an exploding present, or near-future.

This optimization is at odds with the goal of preservation into the far-future. Today's solutions are evolving in the direction of increased complexity, intensity, and resource requirements, so they are inherently less stable in the long run. What we need is a solution that drives toward stable, zero-consumption, zero-requirement for technology at all. A final resting place that can endure every kind of change we have ever seen or will ever see.

Thinking back to the stone carvers. What made stone such a successful medium to carry messages through the eons? In addition to its material property of permanence, it can easily be researched because it does not require any other device to decode or perform. It is what it is. All we have to do is look at it and work out the symbols.

So how can we apply this to data?

We can create a system where we can elect specific data to be permanently archived, and that information is milled, etched, or lazed into a very stable material and stored in a physically stable and politically neutral area. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault comes to mind as a place that would fit the bill.

The material itself contains the text, images, sounds of the source encoded into the physical medium. The encoding schemes will be biased for simplicity (usually at odds with output length), with a consistent metadata/data layering.The materials will be on serialized plates, with a checksum hash of the plate's contents + the prior plate's hash, to ensure information integrity.

The facility maintains an inventory system as well, using the same physical storage technology. This allows for efficient retrieval of stored materials, as well as further integrity checking, as the plate's checksum will be present in the inventory system.

Encoding can be eight bits with two parity bits, or 1024 possible etching/milling positions per datapoint (10 bits total). The length of the metadata envelope is given in the initial bits, followed by a zero. The metadata envelope can then be consumed, which must include a Content-Length, Content-Type, and a Content-Encoding value.

Each possible Content-Type and Content-Encoding would be well documented in plates of their own, encoded in the most rudimentary form possible (e.g. raw ASCII text).

Information-wise, plates must be self-contained. Said another way, the information on a given plate must not depend on a prior plate's contents. Therefore, source information must be split apart into plate-size pieces, each able to supply the data it contains on its own. For instance, if we were digitally encoding the Mona Lisa, the plate containing her smile may be destroyed at some point. The remaining plates could still be used to visualize the rest of the painting. Or if we were storing the digital representation of Moby Dick, we may be missing a plate (which could be a page or more of the book), but the rest of the story would still be readable.

The plates will be placed into air-tight containers, each labeled with an identifier and master checksum. The mapping between container identifier and plate identifier is carried out in the inventory system, and the container moved to storage, its location noted in the inventory system. All updates to a container's location in the storage facility are made simultaneously in the inventory system.

By following these guidelines, we will be able to send our deepest learnings, artwork, feelings, and predictions farther into the future than any of our increasingly delicate mechanisms that technology is producing today.